One of the things that is annoying about studying Greco-Roman civilization is all of the things they should have invented but didn’t. After approximately 300 BC, Mediterranean technology stalled. There is no mystery why that happened. Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) had conquered a huge area of the Middle East. After this death in 323 BC, his empire broke up into 4 parts: Egypt, Syria, Turkey and Macedonia. Plum jobs were available in Syria and Egypt, which are much richer countries than Greece, and their new Greek rulers wanted Greek administrators. Greece emptied out, as Greeks sought their big chance elsewhere. They set up slave societies in their colonies.

Philosophy was twisted by Aristotle (one of Alexander the Great’s tutors) to justify slavery. Obviously, as a member of the royal court, Aristotle was not interested in rocking the boat, at all. He liked being a child of privilege. Philosophy, for him, was a pleasurable way to pass the time.

Despite Aristotle and all of the Greek learning, Hodges1 writes:

“… historians have often ignored the appearance of a very mediocre and often dishonest class of lower-grade administrators and civil servants into whose hands was put the running of industry, commerce and agriculture … These men were responsible for all of the technological processes involved in the enterprises they were controlling, yet their recipes for increasing output were seldom other than to employ more labor.”

These lower-grade administrators were, of course, the men wo left Greece hoping to make it big in the new colonies. Given that classicists were much more interested in proving the ‘narrative’: that Christianity was inferior to Humanism, and that the modern world owed everything to Humanists, it is not surprising that they emphasized words over deeds. Achieving technology is not as easy as philosophical speculation. Let’s look at some stupid things the Greeks and Romans did.

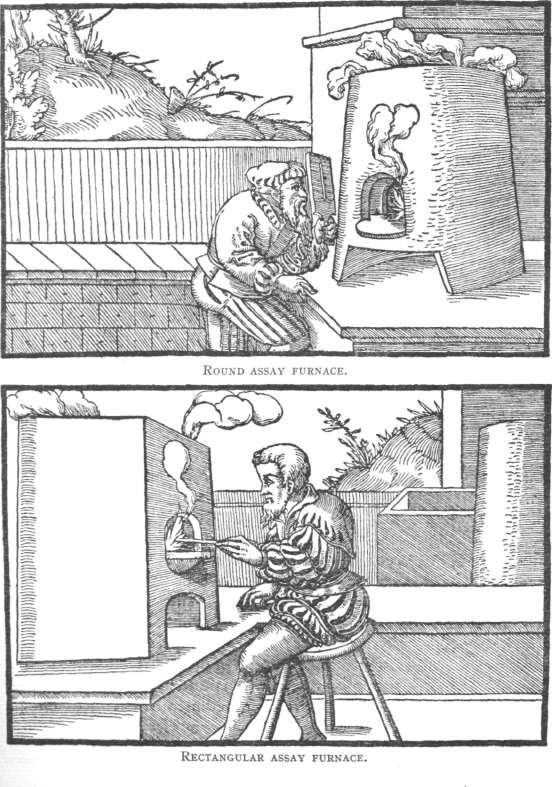

- Cupellation of lead ores to obtain silver.

In the Mediterranean region, a small percentage of silver is often found in lead ores. The silver is recovered from the lead in a process called cupellation. It involves, among other things, melting the ores, and lead is, especially for a metal, a low-melting temperature, volatile metal. It is also a deadly poison.

The slaves they brought in to cupellate the ores and work the furnaces died in months, not years. No one studied the problem to improve the health of the slaves. Even from a business standpoint, this made no sense, since replacing the slaves cost money. The owners were, I guess, philosophical about the situation.

- Harnessing the horse

The way in which the ancients harnessed horses, placed the harness in such a way that it rode up the animal’s neck and choked it when it pulled hard. Everyone could see it, and it was commented on, but NO ONE DID ANYTHING!

Aristotle and his students studied anatomy, but it was too much trouble to apply their studies. Not only was this stupid, because horses could not pull anything heavier than a chariot, it was also cruel. No one cared.

It is scarcely rocket science to rearrange some leather straps. The fact that it was not done until after the end of this period speaks volumes about ancient society. This only changed after Christians began running things, around 400 AD. For over 1000 years prior to that, nothing had been done.

- Horseshoes

In this period, horses were not shod. Romans did try putting shoes on a horse, but these soon fell off. It remained for others to discover nailing an iron shoe to a horse’s hooves. They were adopted by – you guessed it! – Christians.

- Harvesting machines

There actually was a harvesting machine for wheat and other grains invented in Gaul. It was pushed by oxen and described by the Roman writer Pliny the Younger. You would think this boon would be developed and achieve widespread adoption, but nothing of the sort occurred.

The excuse usually given for the ancients was that they had not invented it yet, but in this case, it was invented, and practical.

This illustrates an important point. There are always inventors around. That is one reason why I think that an improved horse harness was probably invented many times, all over the ancient world. The fact that a society adopts a technology and is willing to adopt new technologies is more important than where something is invented. In fact, the Chinese were faster adopters than the Romans, so their technology was very much ahead of Roman technology in this period. Later the European Christians, borrowing furiously from China and other places, would catch up.

- Building ships from outside in

Greco-Roman ships were built in precisely the opposite way to modern ships and boats. The shipbuilder first fastened the planking together and then added interior reinforcements. It’s like building a house by nailing the siding together and then putting in the frame. It’s a strange way of building a large ship, although it is suitable for small boat.

After 500 AD, when the Christians were running things, shipbuilders experimented with building the frame first and then attaching planking. This, much cheaper, way of doing things soon became standard.

- Amphorae (plural of amphora)

Amphorae are the clay pots used to carry wine and other liquids in ancient ships. Because of their odd (but artistic!) shape, when placed in the hold of a ship, about 40% of the space in the ship could not be utilized. This was the empty space around the amphorae. Around 700 AD, in Christian Europe, they were replaced by wooden barrels. Barrels are much more space-efficient; they only waste 10% of the space when packed into a hold. Wood also weighs less than clay, which is a significant factor in how much cargo a ship can carry. Every pound of container material is a pound less of wine or other cargo that a ship can carry.

- Lamps

Romans never invented a good lantern. Lighting was provided by a device of a wick stuck in a pool of oil contained in a bowl made of pottery. This was invented in the Old Stone Age, tens of thousands of years before the period in which we are talking. The only ‘improvement’ the Romans made was to paint obscene scenes on the pottery.

I could go on about the Romans. The average Roman family was poor and lived in a lightly built wood framed tenement. The only air came from a hole in the wall. Heat for cooking came from a wood fire. This fire was open and was built on a stone slab. Fires plagued Roman cities. No one cared about the horrendous loss of life due to fire. These were poor Romans, and only the rich counted in Rome.

Classicists only cared about the fine words and fine art of the Greeks and Romans.

“They (the Greeks) saw both sides of the paradox of truth, giving predominance to neither, and in all of Greek art there is an absence of struggle, a reconciling power, something of calm and serenity, the world has yet to see again.”2

This is the last paragraph of The Greek Way by Edith Hamilton. It is an extended love letter from Hamilton to ancient Greece. This book was assigned reading in high school when I was growing up. Need I add Ms. Hamilton frowns on Christianity, although she concedes that Jesus was almost as good as Socrates. Christianity was excluded from the schools, but classical mythology, the sacred stories of the Greeks and Romans, was taught extensively.

This kind of drivel about Greco-Roman civilization, the so-called classical civilization, deserves our scorn. Hamilton, an upper-class Midwestern Brahman, became headmistress at Bryn Mawr school, a college prep school for women, in Baltimore, MD. None of the miseries of the ancient world ever penetrated her works. Had they done so, I do not think that they would have been so popular.

The ‘calm’ and ‘serenity’ of the Greek artist were purchased at the cost of slavery and untold misery. The appalling cruelty and stasis of Greco-Roman society were never described in Hamilton’s books, and the Greeks and Romans themselves seldom noticed them. The true measure of a society is how the poor are treated, not fine art or fanciful myths. Christians noticed them and began changing the world. The power of the Cross made the modern world, and we must start recognizing that fact, rather than living in a fantasy past.

References

- Hodges, Henry, Technology in the Ancient World, 1970, Alfred Knopf, New York, NY, pp 211.

- Hamilton, Edith, The Greek Way, 1930, W. W. Norton, New York, NY, pp 338.

Sources:

Unger, Richard, The Ship in the Medieval Economy, 600-1600, 1980, Croom-Helm, Ltd., London.

Chapter 1 is an excellent summary of the transition from Roman shipbuilding to Medieval shipbuilding, and the changes in ships and shipbuilding in this period, such as building inside-out.

Hodges, Henry, Technology in the Ancient World, 1970, Alfred Knopf, New York, NY.

Good overall view of ancient technology. Mostly European/Middle Eastern, but also includes sections on China, Indus Valley, and Nomads.

Hamilton, Edith, The Greek Way, 1930, W. W. Norton, New York, NY.

Typical extended love letter to the Greeks. In these books, failings of the modern world are contrasted with Greek achievement. Greek achievement is consistently overestimated. Generations of classical scholars did this to glorify ancient civilization and trash medieval Europe with terms like ‘Dark Ages’. By extension, they were carrying out their bigotry against Christianity.