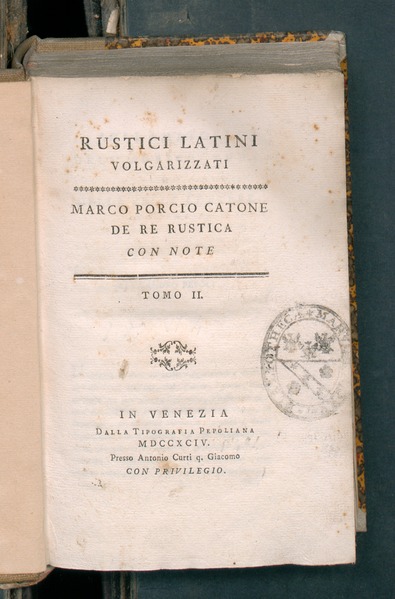

Cato, Marcus Porcius, Rustici latini volgarizzati, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

Cato the Censor (aka Cato the Elder) was a Roman senator who was born in 234 BC and died in 149 BC. He wrote a book, On Farming1, describing two farms. He intended it as a handbook for young farmers. We will take these as examples of Roman farms. On one farm he has a 150-acre olive orchard and the other is a 62-acre vineyard. These are the two cash crops. He also gives instructions for the following:

Wheat (3 types)

Spelt

Barley

Millet

Lentils

Lupins

Field beans

Vetches (2 types)

Fenugreek

Turnips

Rapeseed (an oil plant, Canola oil is a variety of rapeseed oil. Rapum is Latin for turnip.)

Cato values meadows, because in southern Italy forage is scarce in summer. Poplar and elms were planted for forage; their leaves were used in late summer and fall. Italy has a Mediterranean climate; it has hot dry summers and wet, rainy winters. Field crops like wheat are planted in the fall and harvested the following spring. The grain land was ½ fallow and ½ planted. The resting of the soil was so it could recover some of its fertility. The vineyard had 16 slaves and the olive orchard had 13 slaves. There was a slave-foreman and his slave-wife. All work, including supervision, was done by slaves, except for outside contractors.

Cato purchased as little as possible. He advised having a marshy, wet area on the farm to grow reeds and willows for the vineyard. He followed general farming, so many things such as wood for fires, pigs and sheep were raised. The obvious goal as to feed and house the slaves through products from the farm, keep oxen and donkeys for work animals, and buy only the bare minimum outside the farm. The farm also produced delicacies for the owner.

Slaves were given as little as possible and treated like animals. The ration appears to have been about 3000-3400 calories/day1, which is adequate for slaves at moderate work, but less than 70 g of protein, which is not. Since we do not know the exact amount of protein in the wheat grown by the Romans, this can vary.

Protein is made up of amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein. Unless all the essential amino acids are present in the right proportions, humans cannot synthesize protein for muscles and other uses. Wheat is deficient in lysine, which means that unless it is supplemented by other food sources rich in lysine, the wheat protein cannot be used to build the body. Without supplementation, the wheat protein requirement is about 150 g/day because the lysine content of wheat is so low. Many vegan diets are deficient in this amino acid, and this would apply to Cato’s slaves, especially since Cato was determined to feed them as cheaply as possible and meat costs more than grain. Cato, of course, would not know this since modern nutrition was unknown to the ancient Romans. Roman soldiers got the similar rations and probably suffered deficiencies.

Cato’s slaves were given a tunic of 3½ (Roman) lbs. and a cloak once every other year. The translation is ambiguous and could mean the tunic either weighed 3½ lbs., or was 3 feet, 4 inches long. The length specification makes more sense in southern Italy, where a 3½ lb. tunic made of wool would be extremely heavy. These are all cold weather clothing; in summer Cato’s slaves were naked. They wore wooden shoes and were given a pair every two years. When slaves were given new clothes, old ones were taken from him to make patchwork cloaks, and perhaps sell them. Slaves were to understand that everything they owned was the master’s, and nothing, not even their old, worn-out clothes, was the slave’s permanent possession.

Cato’s slaves were housed in the barn with the animals. Pliny (the Elder) reported that his oxen were treated better.

Only one slave woman was specified in Cato’s book, and she was the wife of the slave foreman. None of the other slaves had wives or girlfriends. This was not in the book, but apparently Cato allowed his slaves to accumulate some money. We know this because Pliny reported that he charged a fee to his slaves for breeding. Unless he was running a brothel (legal in Rome) Cato must have had some other slave women on his farms for breeding purposes. After they paid Cato to have sex, their child was owned by Cato.

Criticism

Cato cares nothing for his workers. That marshy area was no doubt mosquito-infested with consequent malaria. He is concerned at all times to show his slaves his power and overawe them. The strongest of them were kept in chains to make them easier to control. All of his slaves would know they could be put into chains or sold to a worse owner.

Every inch of his ground yielded profit. He planted wheat between his olive trees to save money, made sure all of his waste ground was put to use, and kept his slaves as cheaply as possible. White2 makes the point that the farm was ‘efficient’. Slaves can handle difficult tasks (by this logic) as well as free men.

Cato is obsessed with efficiency. Slaves are to be kept busy at all times. Romans, like all slaveholders, feared slave revolts. Manuals of instruction for slaveowners from around the world instruct the owner to ‘keep the slaves busy’. They work every day. There are no weekends and no days off due to weather or holidays. If there is no work to be done on the farm, make some. Keep them tired and worn out so they can’t make trouble. Make them understand their servile status and feel the power of their master. Every minute of a slave’s waking hours is to be devoted to making him money.

Here are some problems with that attitude:

Cato recommends intercropping (planting wheat between olive trees). The FAO3 says it reduces yields of both olives and wheat, especially if the olive trees are full grown. Cato grew up on a farm and this is the way they did it. Which of his slaves is going to tell him this is a bad idea?

Of course, none of them will. It is the slave’s job to obey, not to think. Cato makes it clear that the first job of the foreman is to discipline the slaves. He should never listen to them. Cato advises his foreman to cajole the ox drivers because he will get better work out of them.

The worst idea on Cato’s farm is (probably; it’s chock full of bad ideas) to grow trees for late summer forage. Slaves had climb the trees and pick leaves, and it takes hundreds (maybe thousands) of them to make a snack for an ox. Cato’s problem was that this was a slack time of year. ‘Keep those slaves busy!’, even if it doesn’t pay much.

In Cato’s book is a description of a winery. His wines were abominable, according to his contemporary Pliny4. He tried selling his wines to his friends, but no wealthy Roman would drink his swill. Which of his slaves will tell him that buying cheap, leaky containers and then tarring the inside makes a very poor wine since the tar ruins the taste? Since Cato is Mr. Know-it-all, improving his wines is literally impossible.

Just from this brief description of Cato’s farm, you can see the problem. Cato doesn’t want quality, efficiency or productivity. He wants obedience. Since he doesn’t pay wages to anyone, his farm is almost sure to make money. In fact, Cato made most of his money from usury, not farming. It was not as profitable as he would have liked.

Hiding behind their fine words and fine art is the heartless, thuggish nature of Roman, as well as Greek society. The Greeks also had a slave society, and they were not much better than the Romans in their treatment of them.

The coming of Jesus changed the expectation of what a good society looked like and how it behaved. The (usually upper-class) classical scholars praising Greco-Roman civilization knew about the slaves but did not care. Christians did care and eventually outlawed slavery.

References

1) Brehaut, Ernest, Translator, Cato the Censor on Farming, 1955, Octagon Books, Inc., New York, NY, pp 78-79. The bread ration for fettered slaves (some were kept in chains) was 4 lbs/day in winter. These are Roman pounds, or 13.08 oz (it would have varied because weights had not been fully standardized, and we do not know how accurate the scales were). This was unleavened bread, so we cannot look up modern breads and calculate exactly how many calories that was. According to Pliny, bread exceeds the weight of the grain by 1/3. If we figure the Roman milling practices (their flour was loaded with dirt and grit) this makes sense.

2) White, K. D., Roman Farming, 1970, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

3) FAO, Improvement in Olive Cultivation/by Fernand Paul Pansiot, horticulture specialist and Henri Rebour, consultant, 1961.

4) Allen, H. Warner, A History of Wine, 1961, Horizon Press, New York, NY, pp 72-86.

Excellent description of Cato’s wines and winery from a wine connoisseur.